This is the second installment of a two-part series examining the hardship nomadic herders face in a fast-changing Mongolia.

ULAANBAATAR, Mongolia One afternoon in the mountain pasture where her family had grazed their livestock for as many generations as anyone could trace about 800 miles west of this polluted capital to which she was forced to flee Ishtsooj Davagdorj accidentally ran her sheep and goats into those of another herder, one she’d never seen before. He was from another remote village. As their animals blended and bleated, she blushed. Her heart fluttered.

“He was handsome,” Ishtsooj recalled one afternoon in mid October, a coy smile flashing across her face.

This was roughly two decades ago. Back then, her parents had hundreds of head of livestock but few children to help with herding. They liked the man. Before long, Ishtsooj was married. Children would soon follow. These were happy times in Mongolia. Tall green grass grew on the ocean-like steppe, allowing the herders who still made up the majority of a population smaller than that of Los Angeles to roam a country nearly the size of Mexico. The fall of the Soviet Union, with which Mongolia aligned but never officially joined, brought democracy to a rural nation landlocked between Russia and China.

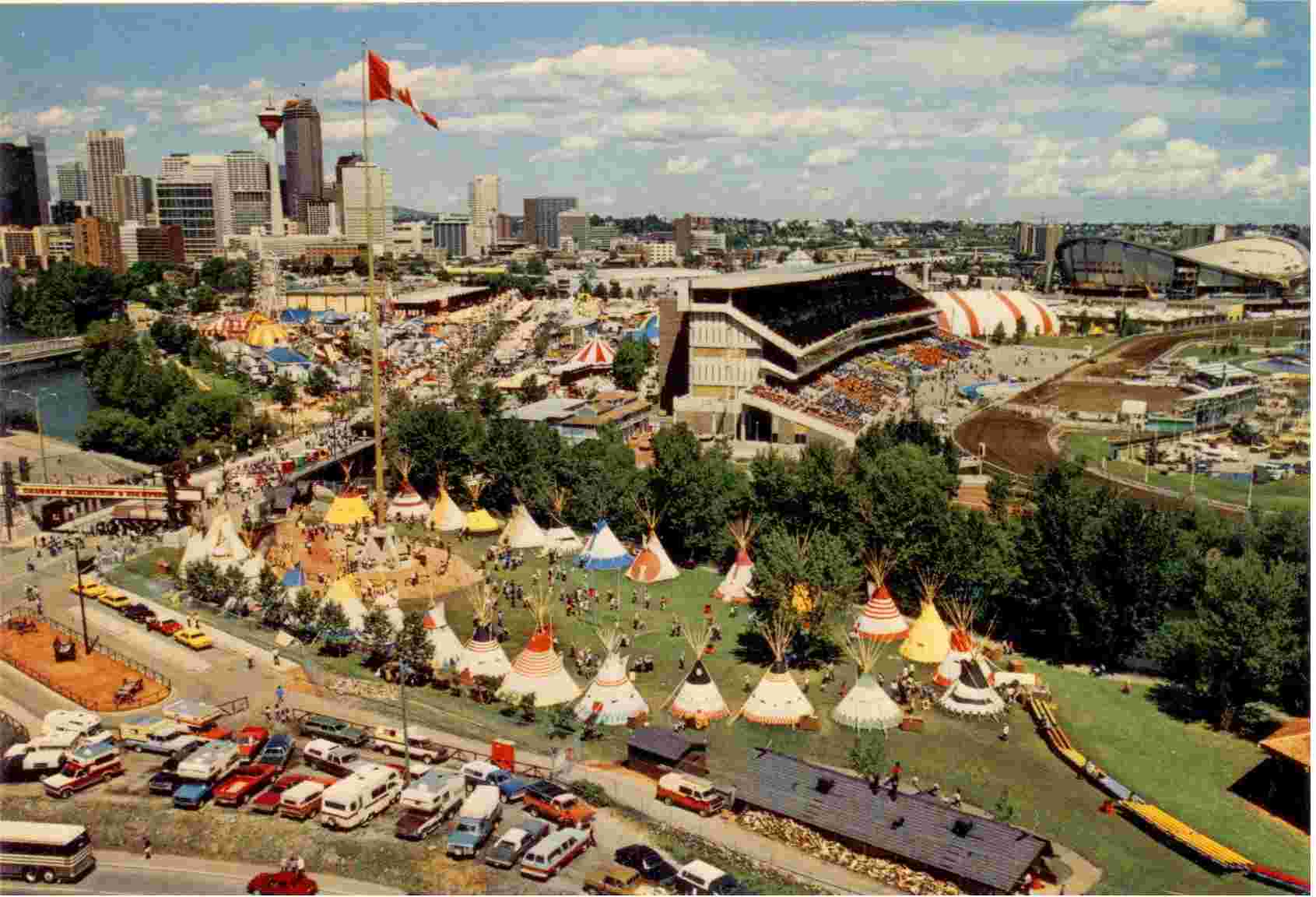

The family lived simply in a traditional ger, the stout cylindrical tents, framed with wood and usually covered in white cloth, sometimes called yurts in English. Their animals the ultimate sign of a nomad’s prosperity numbered more than 400, with sheep, goats, yaks and horses, and as many as four two-humped Bactrian camels used for milk and for transporting their belongings across the northern reaches of the Gobi Desert.

By the late 2000s, however, the weather patterns that had allowed her ancestors to sustain herding practices for millenniums began to change. Each year, the desert crept farther into what were once reliably verdant grasslands. Dust storms, previously rare, became frequent, turning the clear air solid with brown filth that clogged the nostrils and sandblasted the eyes. The summer rains stopped coming. Springs ran dry.

But nothing was like the winter. Mongolians have a word for winters so cold and severe that herds die off: dzud. In white dzuds, snow coats the ground and makes grazing impossible. In black dzuds, the earth freezes, turning vegetation into inedible ice. In the past, a long life on the steppe might see a dzud (pronounced zood) once a decade at most. Suddenly dzuds came year after year. Ishtsooj’s livestock began dying faster than new animals could be born in the spring.

Mining companies, lured by Mongolia’s rich deposits of copper, coal and gold, seized broad swaths of land Ishtsooj’s herds once grazed and left behind craters into which animals fell to their deaths. Wolves came in the night and killed yet more of the herd. As edible grass disappeared, some hungry livestock died gnawing at poisonous vegetation.

In 2009, Ishtsooj took out a loan worth nearly $3,000 to replenish her herd, putting up her existing animals as collateral. But as more died, she missed payments, destroying her credit and placing her on a financial blacklist. By the time she paid off the debt in 2018, she had shelled out almost double the principal in interest.

Ruined, the family saw no choice but to trek across the country to Mongolia’s one big city, Ulaanbaatar, joining the more than 850,000 nomads who have resettled in what are known as the ger districts. The ramshackle neighborhoods ring the city center, with its glimmering new towers and old Soviet-style buildings, covering the treeless hills with what are essentially favelas of ger tents, most of which lack plumbing or access to the electrical grid. More than half of Ulaanbaatar’s population of 1.4 million live in a ger district, and they grow by the month as more nomads give up on pastoral life, migrate to the city’s outskirts and pitch their tent wherever there’s space.

When it rains, at what are increasingly unpredictable intervals, floodwaters sweep away entire homes and spread sewage from makeshift pit latrines throughout entire neighborhoods, triggering flare-ups of diarrhea. When it’s cold, residents burn coal inside, adding to the acrid smog that, combined with the giant coal-fired plants that belch black smoke throughout the skyline, gives Ulaanbaatar the worst air quality of any world capital.

The once-sleepy city wasn’t built for the population explosion of the past decade. There’s no subway or light rail. Traffic clogs the main thoroughfares at most waking hours, contributing even more pollution and making it impossible to get anywhere on time taking the bus. Few of the ger districts have paved roads, much less sidewalks.

For Ishtsooj, who arrived with her family last year, every day is a logistical nightmare. Half of her salary of roughly $200 a month goes to bus fare and gas for the family’s car. After hours in traffic, she makes it home from the restaurant where she works on the other side of the city with just enough time to pick up her sixth-grader son from school and make sure her 10th-grader daughter gets to her evening classes. The schools are overcrowded, with more than four times as many students per classroom as the nomadic schools in the countryside. The kids are bullied by classmates who make nomadic newcomers feel like hillbilly outsiders. High school is free, but a teacher tried shaking Ishtsooj down for $300 to get her daughter into class, roughly equal to a month’s pay for her husband, a delivery driver. Ishtsooj said she must have seemed like easy prey to an educator who knew calling the police about a small bribe would bring Ishtsooj more trouble than help.

And the toxic air is taking its toll.

“My throat is always feeling sick,” Ishtsooj said, clutching her chest to indicate her lungs hurt, too. Last month, a lump on the left side of her husband’s neck got so big they could no longer ignore it. A trip to the hospital confirmed it’s cancer. He hasn’t been able to work over the past few weeks and was in the hospital on the evening when we met in her rented home in one of the city’s western ger districts. As bills pile up, Ishtsooj said, the next move would be to sell the family’s car.

“We used to live in the countryside, where the air was fresh and it didn’t cost anything to go anywhere,” she said. “But now this is normal life in Mongolia.”

‘Traumatized’

In at least one sense, Ishtsooj feels lucky, she said as she rolled dough to fry into cookies called boortsog. She has her children under one roof.

Bor Ankhiluntsetseg’s lonely first year in Ulaanbaatar nearly broke her spirit.

This was more than a decade ago. Bor’s older brother, who had lost his livestock in a dzud, was already living in Ulaanbaatar when, after two years of high school at a provincial school in her native Khureemaral, her parents mustered enough money for tuition to a military school in the capital. She was overwhelmed by its traffic-clogged streets and tall buildings. Navigating the bus routes proved challenging, and she was frequently late to class. The military school had little tolerance for tardiness. The final straw came less than one year into the program, when she became pregnant.

Expelled, she returned home, about 400 miles southwest of the capital, and gave birth. Her parents were furious and said they could not and would not pay for tuition again. A year later, her father dropped dead from a heart attack in the pasture one afternoon, his body discovered among the bleating herd.

Bor had little time to grieve. In shock, her mother soon suffered a stroke. Her daughter was hungry, and there was no money to be made in Khureemaral. So Bor did what many in her generation were doing: She left everyone behind for months at a time to work in the city.

“I was already kind of traumatized. I was used to being loved and cared for by my parents, and then I came to a military school that was so strict,” she told me from her ger on the northern slopes above Ulaanbaatar one morning, a roughly 20 minute drive from Ishtsooj’s neighborhood. “Then I’m very traumatized by the sudden death of my dad.”

One night after a late shift at a dairy factory, she went to a bar with co-workers. Unbeknownst to her, she caught the eye of a young man. He got her number from a mutual friend and began sending her texts every day with poems he wrote and messages of love. She found it corny. But he was so persistent she eventually relented and met him for a date. They both wore white to identify themselves. What was supposed to be a short coffee ended up as a 12-mile walk around the city, stopping for snacks and talking nonstop. She wasn’t interested in a boyfriend, necessarily. She was scarred from the estranged relationship with her daughter’s father, she missed her dad and she longed to be reunited with her little girl so far away.

“I had lost all confidence in men,” she said.

But this man was relentless. He was also gentle and kind. He expressed an interest in her daughter. He had a decent job as a forklift operator at the MCS Coca-Cola Factory, a major food-processing plant in Ulaanbaatar. He worked hard, frequently taking night shifts to earn extra cash.

Bor couldn’t bear living between two worlds anymore. Working all summer in the capital, feeling beautiful in her city clothes, then returning to the country, feeling ugly and covered in muck from herding. It was discombobulating. Her mother had died, six years after her father, leaving her daughter to be cared for by an older cousin. And that was the real heartbreak. Every time Bor left to come back to the city, her daughter would cling to her neck and sob, begging her to stay. Bor would wait until the little girl fell asleep, then head out for the hours-long drive to Ulaanbaatar.

“That’s the earliest memory I have,” said Bor’s daughter, Ankhiluntsetseg Altantsetseg, 17, who uses her mother’s given name as a surname. “My mom was leaving for Ulaanbaatar, and I was holding on to her neck saying, ‘Please don’t go, Mom.’”

A National Identity Crisis

The thought must have crossed Bor’s mind as she hit traffic at the end of her hours-long journey back to the city: Ulaanbaatar wasn’t built for this many people. Driving in from the countryside, the smattering of ger camps, gas stations and industrial lots slowly thickens into a skyline of low-slung Soviet buildings and gleaming new apartment towers, many still under construction. The city center is bisected by the four-lane thoroughfare Peace Avenue, off which the parliament building, the central square, top museums and the main luxury shopping district are located. But a short drive north, west or east veers off paved roads and into ger districts guarded by dogs and haunted by tragic stories of pedestrians who dared walk streets without sidewalks or street lamps.

Is Mongolia a nomadic country or an urban country? That question is coming to us.

- Tserendulam Shagdarsuren, Mongolia's national climate czar

For generations, young Mongols have come to the capital to seek jobs or start new lives.

“It’s the same as in the States. You go to New York. You live in the city. You do the hustle-bustle,” said Bolor Lkhaajav, a U.S.-based researcher and analyst who writes about Mongolia for the magazine The Diplomat . “But here, if you don’t have an apartment, you build a ger. And over time you have unregulated districts. You don’t have the basic infrastructure, you don’t have clean water, you don’t have sewers.”

It’s a symptom of “not planning” for this kind of population growth, said Tserendulam Shagdarsuren, the director general of climate change and policy planning at the country’s Ministry of Environment.

“It is a very difficult situation. U.B. is limited,” she said in a hotel conference room near the government building, using the shorthand most Mongols use for the city’s name in English.

“Is Mongolia a nomadic country or an urban country? That question is coming to us.”

In Emeelt, on the outskirts of the city, a newly built livestock market complex allows herders to cut out the middlemen and sell directly to city consumers. For a little under $6 per day, herders can rent a stall in a roofed market and hawk their animals directly to buyers. A small sheep can sell for about $37, while a big one can go for as much as $100, and all the money goes to the family who raised the creature.

Those who don’t want to pay the daily fee set up shop in the parking lot, selling their animals for slightly less from the backs of their flatbed trucks. Next door, there’s a slaughterhouse that will butcher the animals for buyers looking to bring meat ready to cook back to one of Ulaanbaatar’s growing number of apartments. On the sunny Saturday afternoon when I visited, there were about a dozen cars in the parking lot, most of which appeared to belong to herders or butchers there to work.

“It’s not that popular yet,” Jigden Bayarsaikhan, 32, told me as he showed me around. He runs a pair of tourism and cargo businesses from Ulaanbaatar but grew up in the countryside near the Gobi.

Jigden dreams of making it even easier for herders. Cellphone service and internet connections are widely available throughout the nation, and may even improve now that the government has signed a deal with SpaceX billionaire Elon Musk’s satellite internet service, Starlink. Jigden wants to design some kind of app that would allow herders to sell and ship livestock, meat or dairy products directly to consumers in the city. Such a service would open markets for other players, such as cargo companies that could transport the goods across Mongolia’s vast distances, saving herders the trouble of paying for gas, tolls or the wear the country’s roads take on vehicles.

Tools like that, he said, would help bridge the gap between the city and the steppe, and make it easier for herders to essentially commute remotely into the work opportunities for they might otherwise travel to Ulaanbaatar.

At a modern-looking new community center in the Bayankhoshuu ger district in northwest Ulaanbaatar one afternoon, I met Bilguun Ankhbayar, 19. Boyish but tall, Ankhbayar was a city kid. His grandparents came here 30 years ago, after his grandfather got cancer, and he was born close to this neighborhood in a ger. At 16, he moved into an apartment. But he spends most of his time laser-focused on school. Egged on by his sister, he began studying ecology. He learned English. Now he’s taking French lessons. When he has free time, he said, he studies.

“Other people my age are studying abroad,” he said. “But studying abroad would be too much for me because my parents are still struggling.”

When the whole family is one place, it’s harder to want to leave.

Settling Into The City As A Stepping Stone Overseas

After a few years going back and forth between Ulaanbaatar and her daughter in the countryside, Bor decided it was time to reunite the family, to bring her little girl to the city. She got married and moved into her husband’s ger.

Ankhiluntsetseg, the daughter, was 7 years old when she first saw the city. It was freezing, but her mom and her new stepdad dragged her to Sukhbaatar Square, the central plaza of the capital and home to the national parliament building with its giant nomadic warrior statues. She was overwhelmed. But she was mostly focused on how the refrigerator was stocked with all kinds of treats she’d never had before.

“The fridge was very rich, but we didn’t even have to cook for ourselves,” Ankhiluntsetseg said. “We’d always eat out.”

By then, Bor was pregnant with the first of her next four kids. She stopped working for a while, and money became tight. When Bor went back to work as a civil servant, in a role akin to a city councilor for her subsection of the ger district, Ankhiluntsetseg stepped in to help raise her siblings, especially when the father was working night shifts.

Last August, however, brought fresh upheaval to their lives. Days of rain once an unusual occurrence swelled a reservoir in the hills above the ger district. The dam burst. Cold water gushed through the unpaved roads, filling the pit latrines and spreading raw sewage everywhere. The family’s ger washed away in the wave of filth.

Luckily, Bor’s mother-in-law lived less than a mile away, and the family was able to move in there for a while. But because Bor worked for the government, she was ineligible for the very public benefits she was making sure her constituents received, part of an anti-graft rule meant to avoid perceptions of low-ranking bureaucrats cashing in on their positions.

The family is slowly rebuilding. But Bor’s job depends on the ruling People’s Party winning the June 30 election, since she’s a political appointee and would almost certainly be forced out if another party won power. Ankhiluntsetseg turns 18 on June 2, so she will be eligible to vote. She doesn’t know yet if she will vote for her mom’s party, but either way she isn’t very invested in the future of her country.

“I want to go to Korea and study psychology,” said Ankhiluntsetseg, who is about to graduate from hairdressing school in Ulaanbaatar. “I love talking to people. When people suffer, I think it’s important to listen and talk to them. And I want to live in Korea and work in Korea, and I want all my family to come.”

Her mother said she understands. She herself has thought about moving to Japan, where the salaries are more than twice as high as in Mongolia.

“Deep in my heart, I want to contribute to the development of my country. I really want my country to develop. But the authorities that rule don’t have appropriate policies. And in Korea, it’s just better,” Ankhiluntsetseg said. “Everyone wants to go abroad. So I want to go abroad.”

Mongolia’s problems have no easy fixes, and it could be decades before Ulaanbaatar’s infrastructure comes close to matching the needs of its people.

“You have to have urban planning, limit people from moving into the city, ask people to start clearing out certain areas that are more prone to flooding and natural disaster,” said Lkhaajav, the analyst. “You combine all these issues with how the government is trying to solve it. If you look at the past 10, 20 years, it looks like they haven’t really done anything at all.”

For Ishtsooj, whose family arrived in Ulaanbaatar a year ago, the dream is to get a U.S. visa. Short of that, she wants to go to whatever developed country will take her.

“But how can I go? How can I raise the money? Hopefully my children can someday go to a foreign country,” she said. But even the education required to make her kids competitive to work abroad appears out of reach.

“My daughter wants to be a teacher. My son wants to be a pilot,” she said, then she burst out with an exhausted-sounding laugh.

She leaned in, raised her eyebrows, widened her eyes and raised her voice, as if a louder volume might transcend the language barrier to communicate the absurdity of the situation.

“Two tuitions?” she said through the translator. “How can I pay two tuitions?”

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)