A Deadly Gas

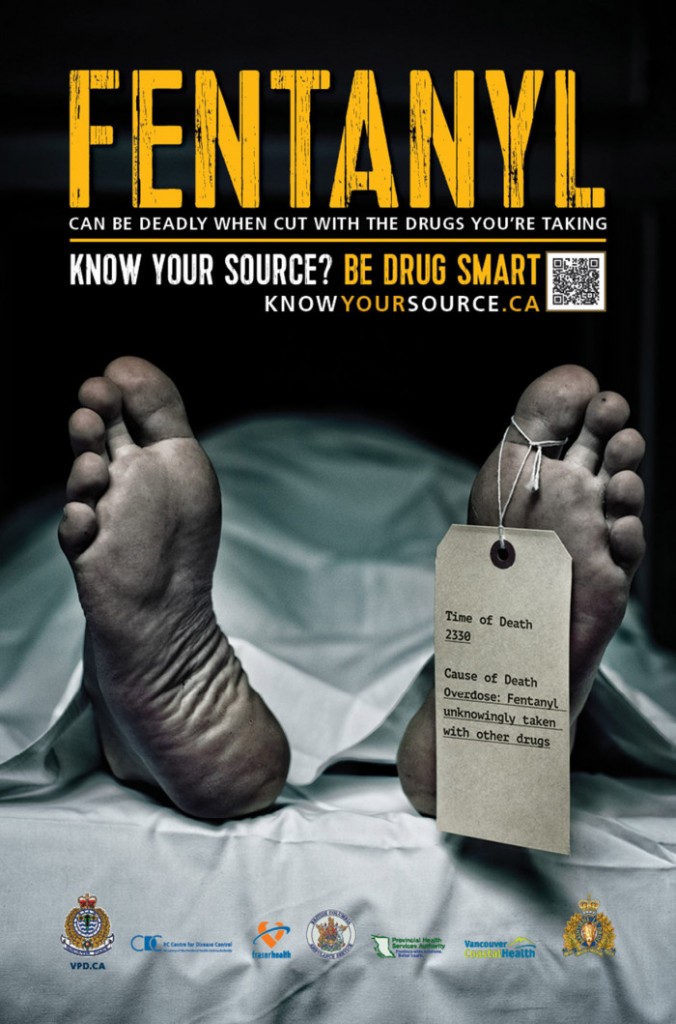

Carbon dioxide has long been used to euthanize laboratory rodents and other small animals, a practice animal welfare organizations now consider inhumane due to the suffering the gas inflicts on the animals. Each year, CO2 accidents kill about 100 workers worldwide often in basements of restaurants that use CO2-charged systems for their bar mixers or in industrial accidents.

Carbon dioxide is an asphyxiant that displaces ambient oxygen, making it more difficult to breathe. Smaller exposures cause coughing, dizziness and a panicky feeling called air hunger. As CO2 concentrations get higher and exposure times longer, the gas causes a range of effects from unconsciousness to coma to death. Even at lower levels, CO2 can act as an intoxicant , impairing cognitive performance and inducing a confused, drunken-like state.

Denburys entire business is built around piping carbon dioxide to oilfields and a few industrial users in two operational centers in the Gulf Coast and the Rockies. It owns or has an interest in 14 oil fields in Mississippi, Texas and Louisiana, which are connected by five CO2 pipelines spanning 925 miles. Among its properties is Tinsley Field, adjacent to Satartia, which became Mississippis first commercially successful oil field in 1939.

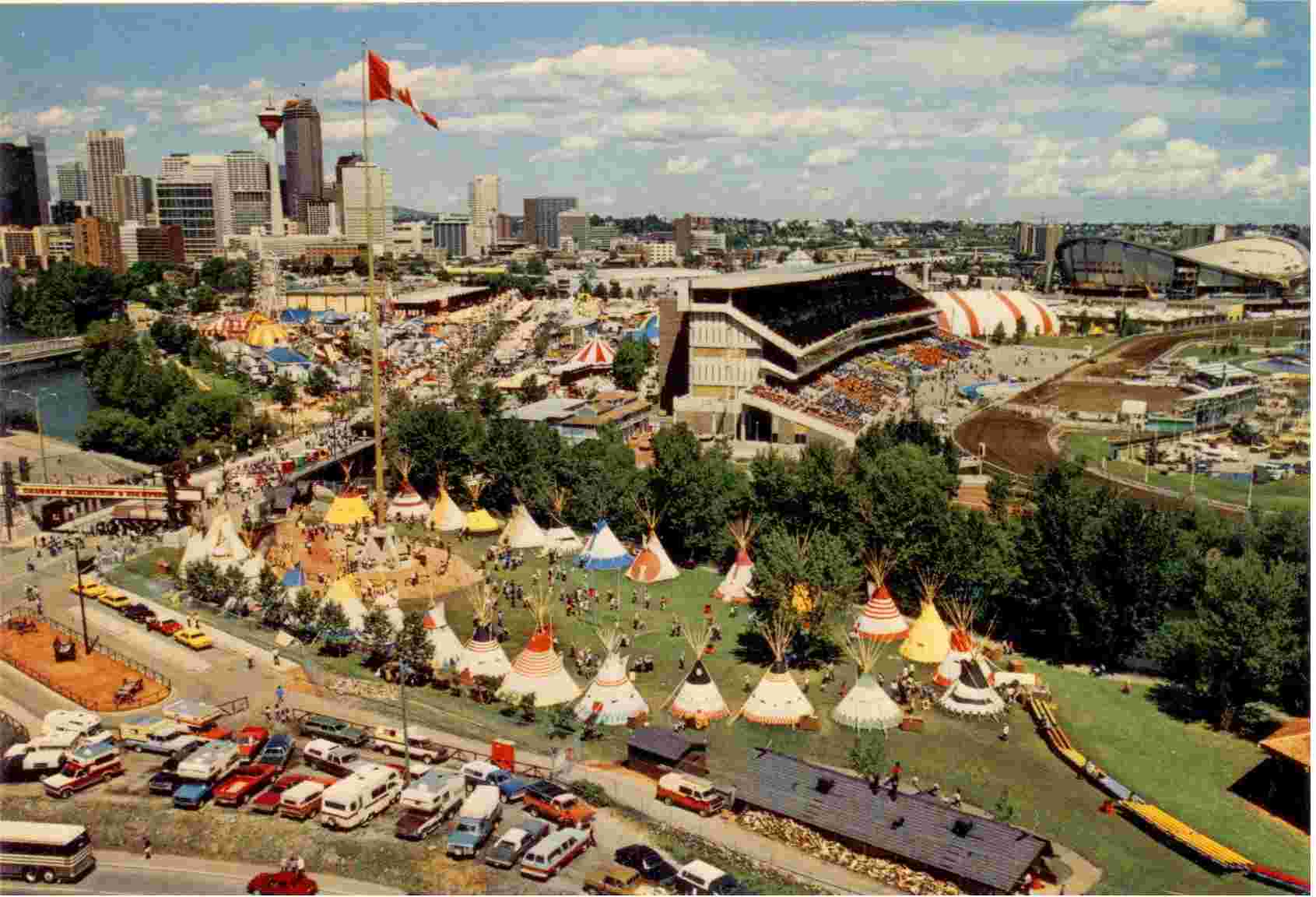

Rory Doyle for HuffPost

In 2007, Denbury built its 31-mile Delta pipeline to connect Tinsley to the Jackson Dome, an extinct volcano under Jackson, Mississippi, whose 4.6 trillion cubic feet of naturally occurring CO2 gas supplies all of the companys fields. Denbury extended the Delta line 77 miles to Louisianas Delhi field in 2009.

Denbury uses the CO2 for enhanced oil recovery, or EOR, which uses the gas to flush more oil out of wells. About 20% to 40% of the oil in a field can be recovered through conventional drilling and injecting water into the reservoir. Injecting CO2 after that can increase the yield up to 60%.

CO2 use in oil fields has resulted in accidents in several states and abroad. Tinsley itself suffered a sizeable CO2 blowout where injected CO2 explodes out of the ground along with water, mud and drilling fluids in 2011 that took 37 days to bring under control, sickened one worker, and killed deer, birds, fish and other animals.

Denbury had already had two other blowouts in Mississippi, one requiring the evacuation of local homes in Amite County in 2007. Another underground CO2 blowout at Delhi field in 2013 lasted for more than six weeks and contaminated the air with unsafe levels of both CO2 and methane.

Denbury and other companies that do EOR are well versed in the dangers of CO2. At Denburys Heidelberg Field in eastern Mississippi, signs warn of a CO2 hazard and say SCBA must be worn, and there are muster stations where workers gather if there is a release. The company also has safety pamphlets on its website one for the public called Pipeline Safety Is Everybodys Responsibility and another for first responders titled, AWARE: Tactics for Responding to a CO2 Pipeline Leak. None of the emergency workers interviewed for this story had seen either.

While the risks of CO2 exposure were well established, the Satartia gassing was the first known instance of an outdoor mass exposure to piped CO2 gas anywhere in the world, according to Marcelo Korc, chief of the World Health Organizations Climate Change and Environmental Determinants of Health Unit, whose staff researched injuries from CO2 pipeline leaks in response to an inquiry from HuffPost.

Rory Doyle for HuffPost

Korcs staff also found that CO2 from the Jackson Dome is contaminated with hydrogen sulfide, a deadly gas that likely worsened residents symptoms and also accounts for the gas clouds odor and greenish color, since pure CO2 is odorless and colorless.

Denbury declined to answer specific questions for this story, sending only a statement:

On February 22, 2020, at approximately 7:00 p.m., Denbury Enterprises Delta pipeline experienced a sudden rupture and release of CO2 gas near Satartia, Mississippi. Before, during, and after the event, Denburys main interest has been the health and safety of the residents in the vicinity of the release and the surrounding environment. Denbury and its personnel were quickly in the community, working directly with nearby leadership and any individual residents affected by the event to ensure that any needs arising from the event were met. We have continued to work closely with the community and have made significant contributions to local emergency response organizations to support the important role they play in keeping the community safe. Denbury has cooperated fully with all federal, state, and local agencies who responded to the incident. The federal agency charged with regulating the pipeline continues its review and investigation of the incident, and Denbury continues to cooperate fully with their efforts.

Beyond the suffering of those who lived through it, the fact that the Biden administration is poised to commit unprecedented billions to carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology putting CCS at the center of the countrys strategy for reducing greenhouse gas emissions further magnifies the importance of Satartias CO2 accident.

The historic hike in federal support for CCS infrastructure includes taking the first steps toward the construction of a continent-spanning network of pipelines in order to move Americas many millions of tons of CO2 to storage areas where, theoretically, the gas can be injected deep underground and sequestered indefinitely.

Some experts estimate this network will need to be as large as or even larger than the 2.6 million miles of existing petroleum pipelines. Meanwhile, there are only 5,000 miles of existing CO2 lines, meaning there is little experience with a wide range of operational and safety issues likely to arise from such a massive new system.

Nevertheless, Bidens climate team; his Department of Energy and three of its former secretaries; most utilities; the coal industry and the governments of several coal states; ExxonMobil, the rest of Big Oil and other major industrial corporations; several climate NGOs; the AFL-CIO; and a bipartisan group that spans both houses of Congress all support CCS and the pipeline expansion in some form.

We want to build more pipes, DOE Secretary Jennifer Granholm told a reporter in June. Theres a lot of jobs that are associated with decarbonizing ... and I think pipes are one of those opportunities.

But the rush to build and operate an integrated CCS and pipeline system has so far taken place with little examination of the safety issue, as the people of Satartia learned.

Korc of the WHO worried that the basic science done long ago on many toxic chemicals, including petroleum products, has never been done for CO2.

The exposure studies simply dont exist, he said.

Satartia was, in effect, an unwitting case study for a monumental project.

Rory Doyle for HuffPost

They Cant Come Evacuate Yall

DeEmmeris Burns was returning to his mothers house in Satartia from a fishing trip with his brother Andrew Burns and cousin Victor Lewis when they heard an explosion and then a deafening roar, like a jet engine. The stench of rotten eggs filled the car.

DeEmmeris Burns immediately thought: pipeline explosion. He knew there was one nearby, but other than its approximate location, knew nothing else about it.

They were driving on Perry Creek Road, a gravel and dirt country lane that hugs its namesake waterway and passes close to but below the location of the pipe rupture. They were almost at his mothers house.

He called his mothers cellphone at 7:18 p.m. and told her there had been a gas explosion.

You got to get out. Were close, were coming to get you, Burns shouted over the roar of escaping gas.

On the other end of the call, 65-year-old Thelma Brown was trying to figure out why her son sounded so strange. He was hollering, breathing heavily, not making sense. She knew the pipeline he was talking about; it runs about half a mile from her house. But she hadnt smelled anything. She heard her son frantically repeating, Cut the air! Cut everything off! Cut the air! And then, silence.

She tried calling him back. No answer. She rang the other two mens cell phones, but got nothing.

Inside the car, the three men rolled up the windows to keep out whatever it was they were driving through. Then the engine died.

Hunh, Burns said. Car shut off.

Minutes later, Thelmas sister, Linda Garrett, who lived just down the road, smelled the gas and called too. Thelma repeated what her sons had told her before their call dropped.

Garrett hung up with Thelma and called 911, but the dispatcher didnt seem to know about a gas leak.

Do I need to be getting out of here? Garrett asked . The 911 operator said shed call her back and let her know.

She cant breathe. Shes on the floor right now

Garrett noticed her own breathing was becoming labored. Then her daughter Lynett Garrett and 14-year-old granddaughter, Makaylan Burns, who had been out picking up a pizza for dinner, staggered in the door.

Makaylan seemed to be in full-blown respiratory distress, and Lynett was unable to talk. She pounded on the dining room table and panted.

What is it? Whats wrong? What is it? Garrett shouted.

Makaylan dropped to the floor, unconscious.

Garrett tried 911 again. This time the operator acknowledged that there was a gas leak.

They have shut the highway down because of it. Theyre not letting anyone in, they cant come evacuate yall, she said.

Garrett was afraid if they left the house, all three of them would pass out. She insisted on an ambulance. The dispatcher said one would meet them outside of town.

Rory Doyle for HuffPost

Garrett and Lynett carried Makaylan out to the car. Garrett had a bad back and both adults were having trouble breathing, but they managed to get the teenager into the back seat, still unconscious.

Lynett drove and Garrett stayed on the phone with 911 as the operator told them the best route out of town. But after a few minutes, Garretts breath just cut out. We aint going to make it, she said, before she blacked out. Lynett drove to where they were supposed to meet the ambulance, but it didnt show up, and she had to drive to the hospital.

Back at her house, Thelma Brown ran outside to round up her 8- and 3-year-old grandchildren. She brought them into her bedroom, along with her 2-month-old grandson. The oldest, who has asthma but hadnt suffered an attack for some time, was having trouble breathing, so she gave him his albuterol inhaler. She gave some to the 3-year-old too, since she had been outside. Brown closed the windows and blocked air from coming in under the door with a wet towel.

Other relatives called, urging her to get out. But her pickup had a flat, and she was alone with three children. Her daughter was supposed to come get the kids after work, but called and told Brown that all the roads into the area were blocked off. Garrett told Brown what 911 had told her: that emergency workers were not coming into town to evacuate victims.

I talked to the Lord. I said, Lord, me and these kids going to bed, recalled Brown. And I said, Were going to stay here until somebody comes and gets us out of here.

She waited for her son and the others to show up. She fell asleep.

Rory Doyle for HuffPost

At the same time, a group of friends were cooking crayfish and sipping beer at a fishing camp along the Yazoo River. It was getting dark when Hugh Martin noticed the rotten egg smell. Soon they were all wheezing and breathing hard. Martins friend, Casey Sanders, collapsed onto the ground, then quickly came to.

Coughing and choking, everyone somehow made it to their vehicles. Martin jumped into his white pickup truck and drove up onto the levee that separates the town from the river. The glare of his headlights illuminated a green, misty fog. The suffocating feeling was nearly intolerable. Only thing I been through worse than this was the gas chamber when I was in the Army training for Desert Storm, he said. And that was CS gas. CS gas is a type of tear gas.

He called his elderly mother, Marguerite Vinson, who told him she was feeling dizzy.

Got your shoes on, mama? he asked, trying to keep the anxiety out of his voice. He told her to meet him in the carport of their home, not far from the fishing camp. After stopping once to throw up out of the truck window, he made it home.

I saw mama standing there, holding her phone, and she was weak at the knees. And I just grabbed her and throwed her in the truck, said Martin. Then I just took off and headed for the highway.

At the stop sign at Route 3 was a checkpoint, but he blew by it, heading north to the hospital in Yazoo City. His mother lay motionless on the passengers seat: Her eyes were open, but she stared blankly ahead when he spoke to her.

At the hospital, he found others from the crayfish cook, including Casey Sanders, and learned that her teenage son, Nathan Weston Sanders, and his girlfriend were missing, after leaving the fishing camp minutes before the explosion.

The girlfriend had called in a panic their pickup was dead, and Nathan Weston Sanders had collapsed. She couldnt revive him and didnt know where they were. Now, Sanders father and another man from the crayfish gathering were driving back into the fog to look for them.

An Improvised Response

Sheriffs Officer Terry Gann was at a grocery store, taking a break from a long day working a double homicide when he received an EMS alert about a motorist who had a seizure due to a green fog crossing Route 433 east of the town.

My friend, shes laying on the ground, shes shaking, shes drooling out of the mouth

Yazoo is Mississippis biggest county at 923 square miles, but its an economically disadvantaged one, with just 11 sheriffs officers who get called in for everything from tornadoes and floods to industrial accidents. Even though he is the countys only criminal investigator, Gann works the disasters too. At 7:32 p.m., he headed toward Satartia in his truck.

EMS advised responders that self-contained breathing apparatus was required to enter the hot zone inside the roadblocks, where the gas had settled. Gann didnt have SCBA with him, but he went in anyway.

At the command post south of Satartia on Route 3, a man told Gann his daughter had gone missing in the gas plume, not far from the ruptured pipe. The cloud was moving slowly northwest, so first Gann took the road over the levee to enter the village from the south to evacuate any remaining residents.

Rory Doyle for HuffPost

He did a round of checks on houses, banging on doors and peering through windows, but found no one. Around him he saw and felt the cloud. Its like I just ran a mile as fast as I could. My ears were popping. My face was burning like a sunburn.

His pickup also started to choke on the fumes. He raced back over the Yazoo River, out of the cloud, to catch his breath and get the vehicle running, then returned to check more houses. Just outside of town, he found a young man and woman pacing the middle of an intersection.

It was almost like something youd see in a zombie movie. They were just walking in circles, he said. I kept telling em, Yall get in the truck. And they would just look at me with this blank look on their face. And the girl was holding a phone up to her head but she wasnt saying nothing. ... Finally I just yelled at em, I said, Get in the truck or youre gonna die!

Gann shoved the dazed teenagers into the back seat, not knowing it was Nathan Weston Sanders and his girlfriend.

After picking up a woman he found unresponsive in a stalled car, his engine began sputtering again, so he returned to the command post to meet the ambulance. By the time they got there, Gann himself could barely breathe and had to be given oxygen.

He did one last search of Satartia, then messaged dispatch, Everyone evacuated at 9 p.m. He radioed that he was heading for Perry Creek Road, which hadnt yet been searched.

That worried Jack Willingham, director of Yazoo County Emergency Management Agency, since Gann had been breathing high levels of CO2 for nearly two hours and was panting audibly over the radio. His speech was often slurred and when it wasnt, it didnt always make sense. Willingham ordered Gann to leave the hot zone immediately and get medical attention.

But Gann, disoriented by the lack of oxygen, got lost and never made it to Perry Creek. With radio guidance, he met an ambulance that took him to a hospital in Yazoo City. After two hours of oxygen treatments, he went home, utterly spent.

Finally I just yelled at em, I said, Get in the truck or youre gonna die!'

By then, however, a three-man team of Vicksburg firefighters was on its way to Perry Creek Road.

They were driving a UTV, or utility task vehicle, a small ATV-like two-seater with an open cargo bed in back that held spare air bottles and tools. Jerry Briggs, fire coordinator for Warren County, squatted in the cargo area with Warren County 911 director Shane Garrard, while Lamar Frederick, a Vicksburg fire chief, drove. Each wore 60 pounds of fire protective clothing and gear, including SCBA.

After making their own fruitless search of the village, they decided that rather than return empty handed, they would enter the blast area via Perry Creek Road. The roar of the ruptured pipeline was deafening as they approached.

A half mile up Perry Creek Road, they saw a car with its lights on and windows up just as the UTV began stalling.

We got victims, Frederick yelled above the roar.

Inside the small red Cadillac sedan were three men: DeEmmeris and Andrew Burns, and Victor Lewis. DeEmmeris Burns lay across the backseat in the fetal position. The other two were slumped against the windows, white foam coming out of their noses and mouths, their clothes stained with urine and excrement. The firemen thought they were too late.

The doors were stuck, so Briggs smashed the right rear window. The three were still breathing, though just barely. The rescuers shook them and tried sternum rubs, but got no reaction.

Rory Doyle for HuffPost

Panting in exhaustion and sweating under all their gear, they managed to get all three out and cram them into the UTV.

They headed toward the south command post. After a few minutes of fresh air, the victims began to stir. Then they tried to stand up. They seemed about to fall off when a truck full of county deputies met up with the UTV, and one of the deputies bear-hugged the men into place until they met the ambulance.

The firemen had just a few minutes to breath fresh air and chug water before Willingham sent them to evacuate a group of mostly elderly residents just across the river. Willingham and the National Weather Service office in Jackson were tracking the plume as it headed northwest, and Willingham was determined to get ahead of it.

By now, six Denbury officials had arrived on the scene along with Denburys air monitoring contractor, the Center for Toxicology and Environmental Health; the environmental remediation firm E3; an investigator for the federal Pipeline Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA); and officials from the Mississippis Emergency Management Agency and Department of Environmental Quality.

At 11:06 p.m., the Denbury team observed no product coming from the failure location, according Denburys report to PHMSA. The leak was officially declared over.

A Massive Buildout

Once the province of a few policy wonks and coal companies, shipping carbon dioxide and storing it underground has gotten much more mainstream attention in recent years amid a tsunami of conferences, draft legislation and interest groups.

The fossil fuel industry has gotten behind CCS as a technology that, it hopes, would allow continued production so long as the emissions are buried underground. But the immense network of pipelines needed to transport carbon dioxide to locations where it would be stored deep below ground werent discussed publicly until recently, nor was how such a rapid, unprecedented pipeline buildout could be done.

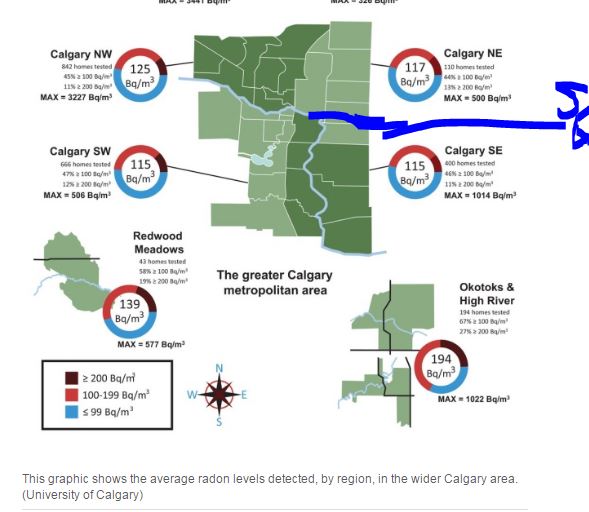

A much-touted December 2020 Princeton University study funded in part by the oil industry calls for a 65,000-mile system by 2050, which means adding 60,000 miles to the current 5,000 miles of CO2 pipeline. The new system would be organized into a spider web of continent-spanning trunk lines as large as 4 in diameter twice the size of the Satartia pipeline fed by a system of smaller spur lines.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)