As a FedEx worker makes her first delivery of the day, she wheels a stack of boxes up a ramp to enter an office building. The automatic doors slide open; one elevator trip later, her delivery is complete. She spots a restroom sign and uses a single-stall bathroom on her way out. By the time she exits, this employee has used at least five accessible features to do her job.

These features seem commonplace today. But many are the result of a protracted fight for equality for people with disabilities, who for decades were left out of buildings they were unable to enter, and who lost out on jobs because employers couldnt and wouldnt accommodate their needs.

As the coronavirus pandemic forces businesses to adapt to a new reality of social distancing, almost all workers suddenly find themselves needing extensive accommodations to keep working. And many companies have been quick to make changes embracing remote work and reenvisioning how people enter and move around workspaces to ensure a safe return to the office (should they return to offices at all).

Costs, long cited as obstacles to modifications despite research showing that the majority of accommodations are free are scarcely an issue. There appears to be a dawning awareness from companies that accessibility benefits everyone, not least their own bottom line.

Its an I told you so moment for the disabled community, said Stephanie Woodward, a crime victims attorney who runs a disability rights website.

Many people with disabilities see this momentum as bittersweet it has affirmed the kinds of workplace policies the disability movement has been pushing for decades, but has been accompanied by the frustration that employers take notice as soon as their non-disabled staff express these needs. In the span of weeks, long-resisted accommodations turned out to be not just feasible, but embraced in the pursuit of productivity.

If able-bodied people need it, its just the price of doing business as normal, said Deborah Dagit, a disability and inclusion expert.

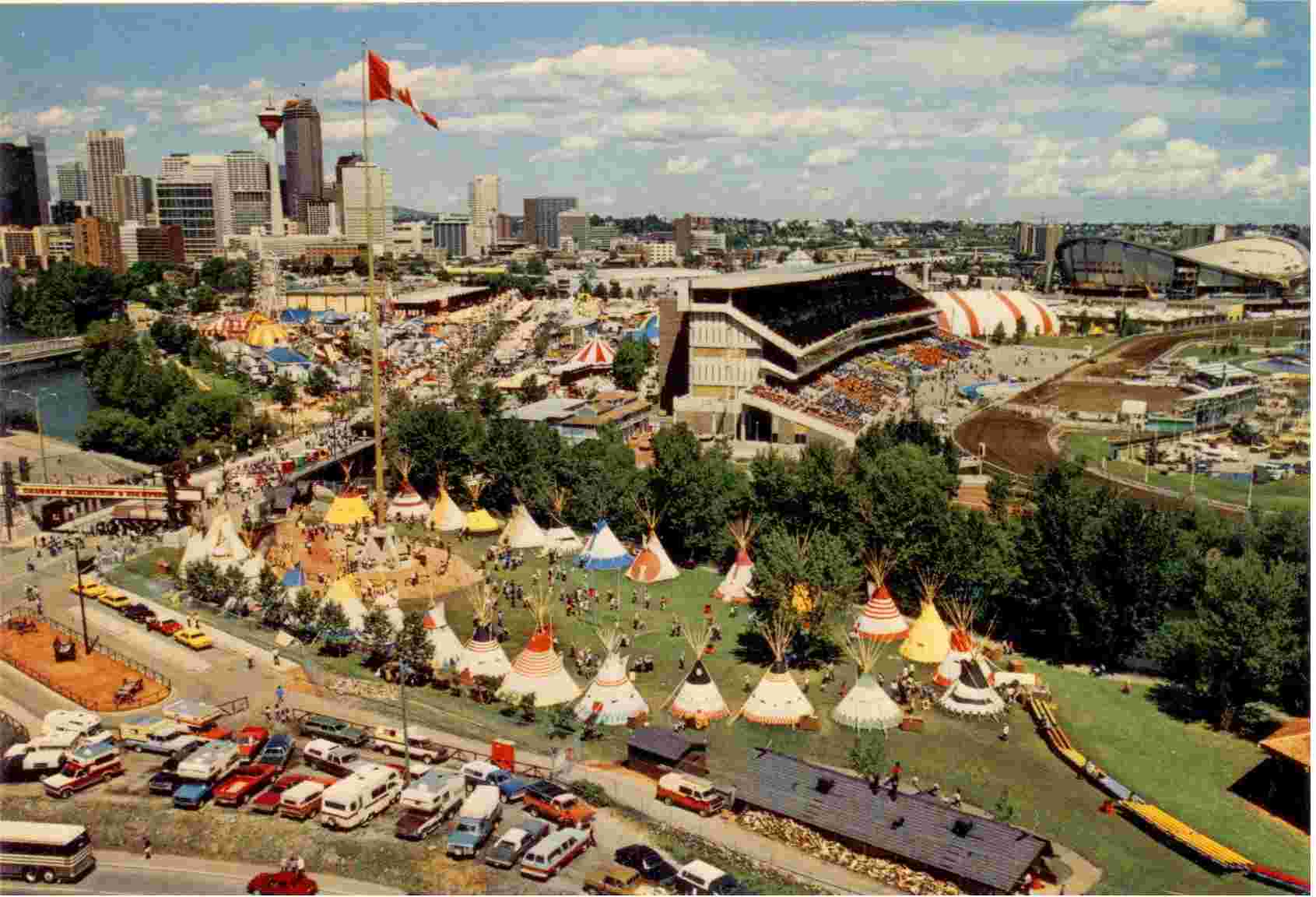

Every day, Americans navigate spaces that were transformed by decades of disability rights activism. Spurred in part by the successes of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, disability advocates won a cascade of legislative victories, chipping away at infrastructural norms that prevented people with disabilities from moving around their cities the way their able-bodied neighbors did. The efforts culminated in the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA), the landmark civil rights law passed 30 years ago. The Act included a slew of provisions to promote equal access for the one in four Americans with disabilities (today totaling 61 million people) across all facets of public life from education, to transit, to the workplace.

_(720p).jpg)

OFFICIAL HD MUSIC VIDEO.jpg)

.jpg)